Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

High on this ridge, fruit doesn’t grow by accident. It grows because the land allows it—because the wind moves through at the right angle, because the soil drains quickly after a storm, because the sun hangs long enough to warm each slope. Everything here is earned. Nothing is rushed.

Fruit of the Ridge is the story of how we grow fruit in partnership with our landscape. It’s an orchard, a vineyard, and a growing ecosystem shaped not by high input farming, but by observation, patience, and an abiding respect for the land itself.

This ridge gives us challenges—late frost, fast wind, dry stretches—but it also gives us purity of flavor, resilience in the soil, and a growing season that rewards diversity.

We grow:

Each variety was chosen not only for flavor, but for how it fits into the ecosystem—how it feeds our bees, how it supports cross-pollination, and how it strengthens the ridge year after year.

This combination shapes every aspect of the fruit we grow:

The steady wind that moves across the ridge helps reduce fungal pressure, meaning healthier peaches, apples, and berries without unnecessary interventions.

Cool nighttime temperatures slow ripening just enough to deepen flavor—especially in apples like Arkansas Black and Winesap.

Water moves downhill. Roots reach deeper. Trees become sturdier, more drought-tolerant, and better anchored for Tennessee storms.

The elevation acts as a buffer, reducing some pests that struggle to climb or thrive in ridge air patterns.

This land demands care, attention, and respect—and it gives back fruit with character, complexity, and unmistakable ridge-grown flavor.

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

Apples are the long game on a ridge. They take time to establish, time to anchor, time to show who they are. But once they settle in, their resilience and flavor are unmatched.

Our apple varieties include:

Apples benefit immensely from cross-pollination.

Our ridge rows are intentionally planted so overlapping bloom windows increase fruit set and quality. Pollinators move easily across open-air lanes, carrying pollen between cultivars.

Apple season is late, slow, and steady—cool nights, bright days, and fruit that deepens in flavor long after it turns color.

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

Pears are some of the most forgiving fruit trees for ridge environments. They love full sun, adapt gracefully to shifting weather, and hold steady against wind. Their blossoms arrive as soft white clusters in early spring, glowing against the hillside and signaling the orchard’s full awakening.

We grow:

The Pineapple Pear brings a distinct addition to the grove. Its fruit is exceptionally firm, lightly aromatic, and well-suited for both fresh eating and canning. It thrives in hot Southern summers and performs reliably in tough conditions, making it an ideal fit for ridge-grown fruit.

Our pear varieties overlap naturally in bloom, creating a soft, extended wave of flowers that feeds pollinators early in the season. This intentional mix strengthens cross-pollination, improves fruit set, and keeps the ridge alive with activity long before other crops awaken.

.png/:/rs=w:370,cg:true,m)

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

Peaches are the early crown of the ridge. They bloom beautifully, they demand careful pruning, and they reward patience with fruit that tastes like sunlight itself. We grow varieties that thrive in heat, wind, and the quick-drying soil of our slopes.

Our peach varieties include:

Though peaches are self-fertile, they still benefit from pollinator activity and the presence of multiple varieties. Their staggered blooms provide early-season nectar, helping our bees build strong colonies after winter.

Pruning here is a conversation with the tree.

We shape for:

When peaches ripen, the orchard fills with warmth and color—a rhythm that feels both fleeting and deeply grounding.

.png/:/cr=t:7.71%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:84.59%25/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

Blueberries love our ridge soil. It’s light, drains fast, and can be amended into a beautifully acidic bed that feeds roots and supports heavy summer fruit.

We grow:

Blueberries rely heavily on cross-pollination among rabbiteye varieties. By mixing cultivars across the slope, we increase berry size, sweetness, and overall yield. Their blooms feed pollinators early in the season, and their fall foliage paints the ridge in warm reds and golds.

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:0%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:100%25/rs=w:370,cg:true)

.png/:/rs=w:370,h:278.1954887218045,cg:true,m/cr=w:370,h:278.1954887218045)

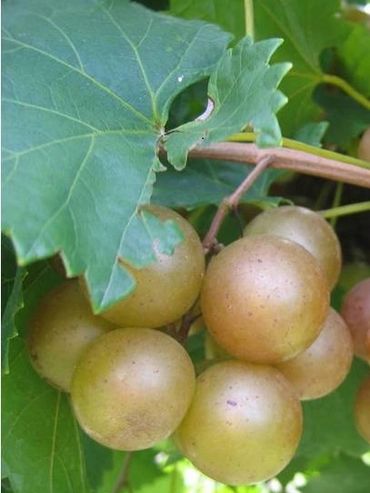

Muscadines are built for the South—heat-hardy, disease-resistant, and deeply rooted in regional history. On our ridge, they flourish. The slopes warm early, breezes push through the canopy, and the vines climb their trellises with unstoppable energy.

We grow:

Some muscadines are self-fertile, while others benefit greatly from nearby varieties. Our rows are arranged so pollen travels freely along trellised lanes, ensuring excellent cross-pollination, consistent fruit set, and heavy clusters down the vines.

Their late blooms also keep the ridge alive with pollinators long after other fruits have finished flowering.

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

.png/:/cr=t:21.88%25,l:0%25,w:100%25,h:56.25%25/rs=w:370,h:185,cg:true)

Blackberries thrive on ridge light and airflow. Our vineyard sits along one of the sunniest stretches of the property, where the soil drains quickly and the vines can stretch into long, fruit-heavy arches.

We grow:

These varieties bloom in sequence, extending nectar availability for our pollinators and ensuring consistently high fruit set across the vineyard. The ridge wind dries morning dew quickly, reducing moisture-related issues and helping berries develop firm, concentrated sweetness.

Harvest days smell like warm fruit and clean soil—the kind of scent that stops you mid-step because you can’t help but take it in.

We didn’t choose varieties for convenience—we chose them for compatibility.

On this ridge, overlapping bloom times are essential:

Our bees move from peach blossoms to pear clusters, from blueberry bells to blackberry blooms, and finally into muscadine flowers. This continuous progression of forage strengthens the apiary and deepens the health of every fruiting plant on the ridge.

A diverse orchard is a resilient orchard.

And a ridge filled with staggered blooms becomes a sanctuary for pollinators that, in turn, strengthen the land.

Everything we do begins with the soil. Our approach is intentionally slow and regenerative:

Watering is deep and infrequent to encourage strong root systems—an essential trait for ridge-grown fruit.

The result?

Trees and vines that don’t depend on constant human intervention.

They don’t panic in drought.

They don’t collapse in storms.

They grow with the rhythm of the ridge, not a schedule on paper.

Ridge-grown fruit tastes different because:

Blackberries grow firmer.

Apples deepen in color.

Peaches ripen with complexity.

Muscadines burst with concentrated sweetness.

This is terroir in its truest sense—the land speaking through the fruit.

Fruit of the Ridge is still young, but every year it grows deeper, stronger, more integrated. Our long-term vision includes:

This ridge is becoming not just a farm, but a living, thriving ecosystem rooted in biodiversity.

Every tree and vine here was planted by hand. Every blossom is visited by bees raised just a few steps away. Every harvest carries the weather, the soil, and the story of this ridge.

Fruit of the Ridge is more than an orchard.

It’s a relationship between land and grower—a slow, season-driven partnership that deepens year after year.

And this is only the beginning.